Gorillas in the Mud

Mountain Gorilla Excavations in the Virungas

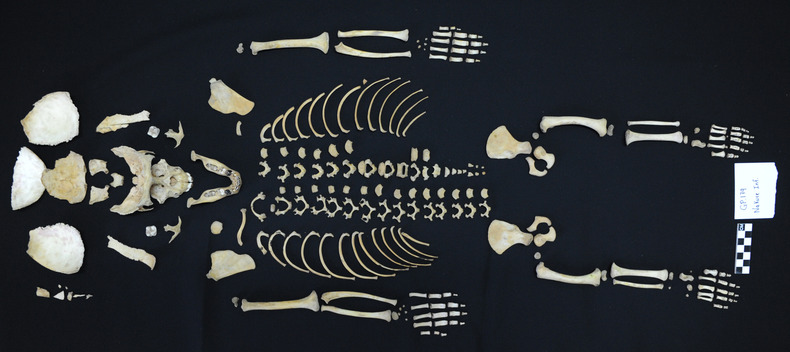

These juvenile gorilla bones contain crucial information about living mountain gorillas. They document important life events, such as when the gorilla was weaned from its mother or whether it suffered any diseases or periods of stress. This information helps scientists understand how best to conserve mountain gorillas for future generations and informs our understanding of the evolution of apes and, ultimately, ourselves.

The gorillas of the Virunga Mountains have been a source of intense public interest since Dian Fossey’s highly publicized studies of the population beginning in 1967. Recently, these gorillas have entered the public dialogue yet again following the release of the acclaimed documentary, Virunga, which focuses on the grim conservation challenges facing workers in Virunga National Park in the eastern Congo. Fortunately, the situation is much less perilous on the other side of the border, in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park. Here, ecotourism, conservation initiatives, and scientific research are thriving.

This summer I traveled to Volcanoes National Park to participate in the Mountain Gorilla Skeletal Project which focuses on the recovery and curation of skeletal remains of some of the very same mountain gorillas observed by Dian Fossey herself. I joined a team of researchers including project co-leaders, Dr. Shannon McFarlin (a NYCEP alumnus; The George Washington University, GW) and Dr. Antoine Mudakikwa (Rwanda Development Board’s Department of Tourism and Conservation, RDB), research and veterinary staff from project partner institutions (RDB, Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International’s Karisoke Research Center, and the Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project), and students from GW and the National University of Rwanda.

Upon arrival in Rwanda, we were immediately brought to Musanze by colleagues from the Karisoke Research Center. After a few days of preparation, we headed out into the field to begin excavations alongside our Rwandan colleagues. Previously, gorilla remains were buried throughout the park. These days, however, all remains are taken to a centralized location on the outskirts of the park boundaries. When a gorilla dies in Volcanoes National Park, a team of veterinarians from the Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project perform a post-mortem exam, taking fluid and tissue samples for further analysis, before burying the remains in the “gorilla graveyard”. Once the remains have completely decomposed, excavations can begin.

Excavations of large, silverback gorillas are back-breaking. Those large bodies take up a lot of space, and consequently a lot of dirt. On the other hand, juveniles present their own difficulties. The ends of many of their bones (the epiphyses) and the bones of the cranium are often unfused and easily disturbed during excavations. Additionally, the bones are much more fragile than adults and decompose quickly if not removed soon after all the soft tissue is gone. Once the skeletons are recovered, they must be thoroughly cleaned and cataloged before entering the collection. When this lengthy process is completed, the remains are ready for study.

For my research, I gathered 3D surface scans and silicon impressions of the facial skeleton of gorillas of all age classes. These silicon impressions produce a high-resolution replica which can then be used to create a secondary model of the original bone surface. These models are examined under high-powered microscopes to infer the last state of cellular activity on the bone surface. By looking at patterns of facial bone deposition and resorption across all ages and developmental stages, I can learn more about exactly how gorilla faces form. By examining the bones of animals of known age and life history I hope to better understand how aspects of their anatomy reflect their ecology and evolutionary history, potentially illuminating previously unrecognized ways of deciphering the fossil record.

This project was borne out of the collaborative efforts of wildlife veterinarians, skeletal biologists, anthropologists, conservation biologists, and many others who recognized the value of recovering these skeletons for research. Thanks to the efforts of a large team of field-based researchers and other staff who have dedicated their lives to protecting and monitoring Rwanda’s mountain gorillas, and preserving their skeletal remains for study, I look forward to seeing what this collection continues to reveal about the lives of mountain gorillas even after their deaths.

Natalie O’Shea is a PhD student at CUNY/NYCEP studying craniofacial growth and development in fossil and living apes and humans.