How big brains and bipedalism made birth laborious

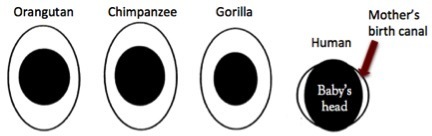

Have you ever wondered why giving birth takes such a long time, hurts so much, and is so dangerous? Seems like a bad idea for a species’ survival, doesn’t it? Maybe you assume that it’s always been that way, or that’s just the way it has to be. Would it surprise you to learn that birth for our closest living relatives, the apes, is a relatively easy process because the mother’s birth canal is spacious compared to the size of her baby? It turns out humans are the odd ones out amongst the apes because our babies’ heads are as big as or bigger than the birth canal! No wonder birth is so laborious.

Image credit: Rosenberg and Trevathan, 2002

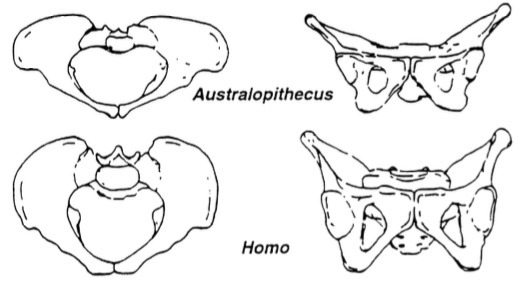

So how did we get here? Why did natural selection favor this strange situation? What stops selection acting to increase the size of the maternal birth canal?. One popular and long-standing hypothesis is termed “the obstetric dilemma”. Basically it posits that to be an efficient biped you need a narrow pelvis (Washburn, 1960). Selection should favor narrow hips for effective and efficient bipedalism and this in turn could constrain the width of the pelvis and thus the birth canal (see Warrener et al., 2015 for a good explanation of the biomechanics involved). In the image below you can see that during hominin evolution the pelvis has changed from being wide in early hominins like Australopithecus to narrow in modern humans. Combine a narrow pelvis with our famously big brains and you have a tricky situation when it comes to squeezing a big-headed baby out of a small birth canal.

Image credit: Rosenberg and Trevathan, 2002

This doesn’t mean that selection has favored maximizing the dimensions of the birth canal. It most certainly has. The human pelvis is sexually dimorphic, which means that men look different to women, and unsurprisingly women have a pelvis that is better adapted to birth. Adaptations include the delayed fusion of the pubic bone’s epiphysis to allow the pelvis to continue widening well into your twenties (Tague, 1994), the ability of the ligaments that hold the two pubic bones together at the front of your pelvis to relax during birth to increase the size of your birth canal (Putschar, 1976), and rotational birth which allows the baby to twist when being born to match the longest dimensions of its head to the widest dimensions of the birth canal (the dimensions of the birth canal are change from the inlet to the outlet) (Rosenberg and Trevathan, 1995).

Image credit: Rosenberg and Trevathan, 1995

So, problem solved, right? Our pelvis can’t get any wider because we would be inefficient walkers, and selection has acted to do everything it can to make sure we can give birth. Well, one problem with this scenario is that despite a lot of research it has not been shown conclusively that humans with wider pelves are any less efficient at walking than those with narrower pelves (Warrener et al., 2015; also see Dunsworth et al., 2012 for an alternate hypothesis).

That’s why instead of looking at constraints placed on the pelvis due to bipedalism (which are doubtless very important) I am going to investigate what role thermoregulation has played in pelvic morphology (Ruff, 1994). Having a narrower body is useful for shedding heat when you live in a hot climate because it increases the ratio of your surface area (skin) to your volume. The more surface area you have, the easier it is for you to get rid of excess heat by sweating or pumping blood to the surface to cool down (Charkoudian, 2003). This is termed Bergmann’s Rule (Bergmann, 1847). Thus we see narrower bodied humans in areas of the world with hot climates such as East Africa, and wider bodied humans in cold areas of the world, such as the Arctic (illustrated below with bears).

Image credit: Loftwork.com

However, although pelvic width does increase with increasing latitude (Ruff, 1994), no one has actually demonstrated that a wide pelvis makes any difference in the human body’s ability to thermoregulate. Therefore I am going to have volunteers run on a treadmill at various temperatures while I take measurements of their core temperature, using an innovative pill that will transmit their temperature to a recording device manufactured by HQInc.

Image credit: HQInc

I hope to find out if hip width coordinates with the ability to maintain a stable or low core temperature during strenuous exercise (such as hunting), as this would have been an advantage to individuals evolving in a hot climate. Hopefully this research will help to explain why, during our evolutionary history, there was a change from a broad pelvis to a narrow one, which made birth so laborious.

For a great review of this topic visit Dr. Bob Martin’s blog

Citations

Bergmann, C. (1847). Ueber die verhältnisse der wärmeökonomie der thiere zuihrer Grösse. Göttinger Studien 3, 595–708.

Charkoudian, N. (2003). Skin Blood Flow in Adult Human Thermoregulation: How It Works, When It Does Not, and Why. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 78(5), 603–612.

Dunsworth, H. M., Warrener, A. G., Deacon, T., Ellison, P. T., & Pontzer, H. (2012). Metabolic hypothesis for human altriciality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(38), 15212–15216.

Putschar, W.G. (1976). The structure of the human symphysis pubis with special consideration of parturition and its sequelae. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 45, 589–594.

Rosenberg, K., & Trevathan, W. (1995). Bipedalism and human birth: The obstetrical dilemma revisited. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 4(5), 161–168.

Rosenberg, K., & Trevathan, W. (2002). Birth, obstetrics and human evolution. BJOG : an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 109(11), 1199–1206. 45, 589–594.

Ruff, C. B. (1994). Morphological adaptation to climate in modern and fossil hominids. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 37(S19), 65–107.

Tague, R. G. (1994). Maternal Mortality or Prolonged Growth: Age at Death and Pelvic Size in Prehistoric Amerindian Populations. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 95, 27-40.

Warrener, A. G., Lewton, K. L., Pontzer, H., & Lieberman, D. E. (2015). A wider pelvis does not increase locomotor cost in humans, with implications for the evolution of childbirth. PLoS ONE 10(3), e0118903.

Washburn, S. L. (1960). Tools and human evolution. Scientific American 203, 63–75.

Jennifer Eyre is a Ph.D. candidate at New York University and a member of NYCEP and CSHO who is interested in the evolution of the modern human pelvis and mechanism of birth.